Revolutionary, formidable and feared, Diocletian is without a doubt one of the most important rulers in the history of the Roman Empire. After decades of turmoil across the Roman world during what is now known as the Crisis of the Third Century, Diocletian rose to prominence after the murder of Numerian. He would rule from AD 284 until 305. His reign was characterized by the creation of what is now known as the ‘Dominate’. This institution essentially lifted the emperor to a god among men – with the emperor donning robes and regalia more befitting of an eastern king than a Roman Emperor, and only accepting visits from a select few individuals.

Diocletian did, however, share his power. He needed a method of smoothing out the nightmarish scenario which had plagued the 3rd Century AD – succession. Time and again a leading military commander had been declared emperor by his troops (Diocletian was no exception), and rose to victory over the current emperor. He would, more often than not, meet his demise under similar circumstances, after a short reign.

The Tetrarchy was conceived as a way to avoid this. The empire would be split in two – east and west. Both would be ruled by an emperor, an ‘Augustus’, as well as a junior emperor, known as a ‘Caesar’. The Caesar’s role was to learn from his Augustus, ready to fill his shoes. The Tetrarchy worked smoothly at first, with Diocletian and his co-emperor in the west, Maximian, abdicating in AD 305 – the first emperors to do so. Their Caesars, Galerius and Constantius Chlorus, stepped up as Augusti. The system was, eventually, doomed to failure with the rise of the Emperor Constantine, but the principle was, in theory, sound.

Another of Diocletian’s many reforms was that of the Roman Empire’s currency. For years, the purity of Rome’s silver coinage had been reduced and reduced until, by the time of Gallienus (AD 253-268) it contained barely any precious metal at all. Attempts had been made by the renowned Emperor Aurelian to restore the coinage, but the people of Rome still had no high-grade silver coins in their pockets, as their ancestors had before them. With Diocletian’s reforms, this would change. Diocletian set an edict on the maximum prices goods could be sold for, with severe punishments for those who broke the rules. He revalued the currency, creating a new silver coin: the Argenteus, and he increased the weight of the gold aureus. Diocletian also introduced a new, large, billon coin: the follis. These were, however, issued in far too great numbers in relation to the silver – affecting the reforms and limiting their success.

This gold aureus was minted in the eastern city of Cyzicus, in AD 290. The style in which it depicts the emperor is a product of the shifting appearance of artistry we begin to see in this period. There is a distinctive move away from the ‘warts and all’ styles of the soldier emperors before him. This move towards a more symbolic ‘emperor figure’ would become much more apparent into the 4th Century AD. The short inscription; Diocletianus Augustus, leaves us no doubt as to the emperor depicted.

On the reverse, we can see the emperor for a second time. Despite donning elaborate, richly adorned clothing in real life, on this coin he can be seen in the more traditional attire of a Roman statesman – a toga. He holds a globe, reflecting his position as a supreme ruler, and a parazonium – a large ceremonial dagger, and a symbol of the emperor’s virtuous nature, and his respect for the military from which he came. The coin itself celebrates Diocletian’s fourth year as Consul – the joint highest-ranking position in the Roman Senate, and a title held by the majority of Roman Emperors. Some have suggested the ‘PP Pro Cos’ refers to the Processus Consularis, an event traditionally held by the Consul on his accession to political office. Some have suggested that this gold aureus may have been given as a donative to guests of the auspicious occasion.

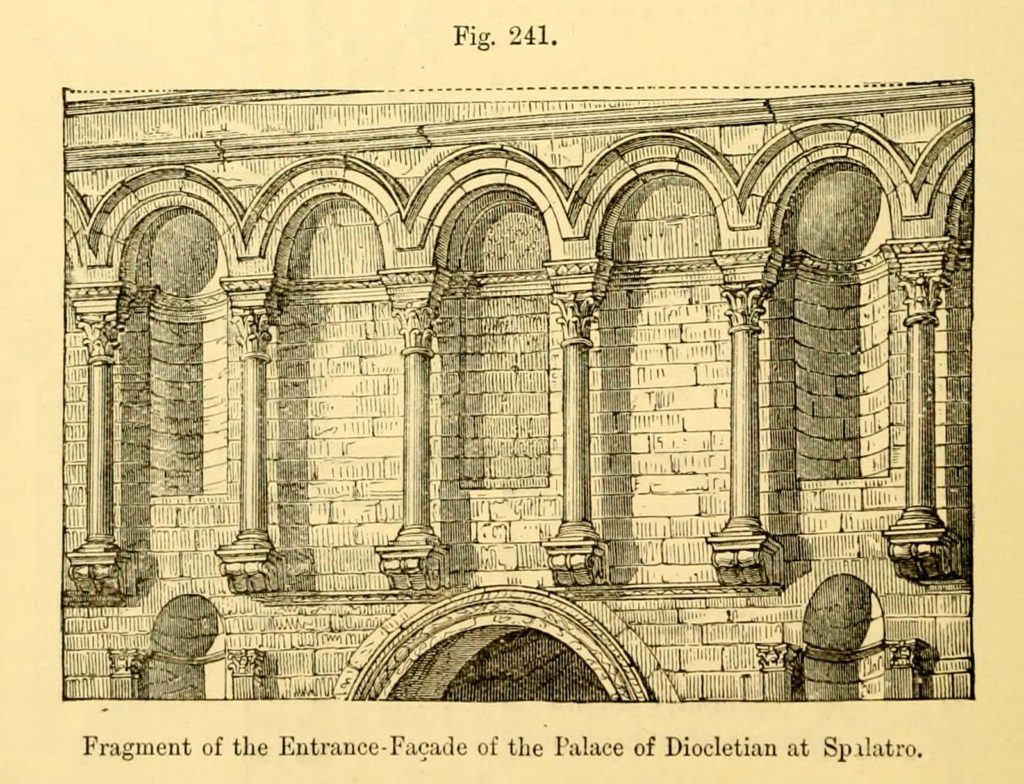

As mentioned earlier, Diocletian is remarkable in being the first Roman Emperor to abdicate voluntarily. In AD 305, satisfied with his sweeping reforms and relative peace and security after the decades of turmoil, he famously retired to his private palace on the Dalmatian coast (near modern-day Split, in Croatia) to tend to his cabbages.

Coin Information

- Ruler: Diocletian (AD 284-305)

- Denom.: Aureus

- Obverse: DIOCLETIANVS AVGVSTVS, laureate head of Diocletian facing right.

- Reverse: CONSVL IIII P P PROCOS, Diocletian standing left, togate, holding parazonium and globe.

- Metal: Gold

- Mint: Cyzicus

- Weight: 5.26g

- Reference: RIC 285

Find out more about Ancient Roman Coins.