Owing to the Government’s recent restrictions on movement as a result of the Coronavirus, the traditional Maundy Money presentation by HM The Queen on Maundy Thursday, the Thursday before Easter, was unable to go ahead. The coins were ready and the recipients chosen, so in a break with an age-old tradition, the coins were blessed in a special service at the Chapel Royal and then posted to the worthy recipients.

The Maundy ceremony has survived earlier plagues; Elizabeth I deputised it to her Almoner in 1563 because of a plague prevalent at the time. Charles I also delegated the task to his Almoner in Oxford in 1643 for the same reason; as a result of the plague, entry into Oxford was forbidden by members of the public, but as the recipients were already within the City the ceremony went ahead. The Almoner is recorded as having bent down and then kissed his own thumb instead of the recipients’ feet. Charles II, who was keen to reintroduce the ceremony which had lapsed during the Civil War and the Commonwealth period, braved an outbreak of plague in 1661 and personally carried out the ceremony. Despite a worse outbreak in 1663, which caused the cancellation of his planned procession and lavish celebrations on his return from his Scottish coronation, Charles II again personally carried out the ceremony.

The ceremony owes its origin to Christ washing the feet of the Disciples. The pedilavium ceremony – washing the feet of the poor – is in memory of this act of humility, and can be traced back to the fourth century in Northern Italy and Spain, and was soon followed elsewhere. The monarchy adopted it when Edward II washed the feet of the poor on 21 March 1326, and Edward III subsequently added gifts of clothing, food and money to the ceremony. The number of recipients was originally twelve, reflecting the Twelve Disciples until Henry IV changed the number so that it represented the monarch’s age. This year there were 94 male and 94 female recipients. The Maundy money is derived from the alms given to the poor; the name ‘Maundy’ is thought to derive from the Latin word Mandatum (commandment), to ‘Do this in remembrance of me’.

The tradition of the monarch personally presenting the coins ceased in 1699, and the washing of the feet ceased in 1737; the actual presentation was then usually carried out by the Lord High Almoner, whose small fee is paid in Maundy money, on behalf of the monarch. However, the monarch did sometimes attend the service, watching from the royal pew in the Chapel Royal, Whitehall, as Victoria did in 1842. Presentation by the monarch was reintroduced in 1932 by King George V and has been continued ever since until today.

The original ceremony of washing the feet is now symbolised by officials wearing aprons and carrying towels, and HM The Queen carries a traditional nosegay – a sweet-smelling bouquet designed to protect the holder from the smell of the unwashed.

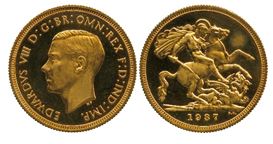

Over the years the number and type of other items given as well as the coins have varied hugely, sometimes including the monarch’s cloak. In the reign of the ‘boy king’ Edward VI extra money was given instead of his cloak, as it would have been too small to be of use, and the number of recipients was raised to twelve. Recipients usually received some clothes as part of the gifts; this tradition lasted for the men until 1882, but from 1724 female recipients received a cash allowance in lieu of clothes, to avoid the unseemly sight of them undressing and trying on new clothes during the service. These extra gifts are now represented by a small cash payment in a red leather purse: the latest issues of a commemorative £5 coin and a commemorative 50 pence, a total of £5.50, which represents £3 for clothing, £1.50 for food and £1 in lieu of the gown.

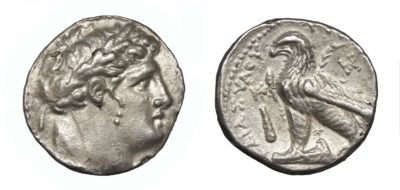

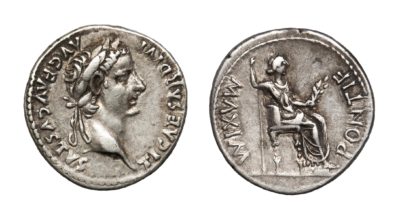

Each recipient is also presented with a white leather purse containing the Maundy coins, which represent the original gift of cash. The Maundy money has been issued as a set of four silver coins, from the fourpence to a penny, from the time of George II or possibly George III, but before that, it consisted mainly of silver pennies. Earlier small silver denominations, although traditionally known as Maundy money, are now thought to have been struck as circulating coins.

Available from Baldwin’s is a set of Maundy Money issued by Queen Victoria, struck in 1875. Queen Victoria was then aged 55, so there would have been 55 male and 55 female recipients, each receiving coins to the total value of 55 pence – five sets (total value 10 pence each) and a few more Maundy coins to the value of five pence, probably mainly pennies. Further examples were made available to the public – between just over 4,000 and nearly 8,500 of each of the different denominations were struck, still a very low issue by monetary standards.

View the set

The 1875 set is in mint condition, as it would have been on the day it was presented, with the addition of some light and pleasant colourful toning acquired over the years of storage. The attractive young head portrait on the obverse is by William Wyon, and the reverses were designed by Jean Baptiste Merlen.

This article is written by Jeremy Cheek, recently retired numismatic consultant to the Royal Collection and world coin consultant for A. H. Baldwin and Sons.