One of the pleasures of numismatics lies in the romance of names, the more obscure, perhaps, the more enchanting. Mervyn Peake, himself could not have invented any more gorgeous and euphonious verbal arabesques than the names of the emperor Didius Julianus, his consort: Manlia Scantilla and their daughter, Didia Clara. These names are today familiar only to the coin collector in pursuit of rarities and to a few surviving ancient historians.

We are fortunate in having three more or less reliable commentaries on the fleeting reign of Julianus. There is an account in Greek by Cassius Dio, who was a consul in the reign of Severus Alexander (222-235). Unfortunately, however, the section of his vast history relating the events of this period survives only in fragments and a later abridgement. Herodian of Syria, writing also in Greek, probably in the reign of Philip the Arab (244-49), also witnessed the events of the reign as a boy, and his account survives intact.

However, the most coherent narrative is that preserved in Latin in the miscellaneous Scriptores Historia Augusta, compiled two centuries later, apparently in the reign of Theodosius I (379-95). This work is a peculiar compendium, claiming to be written by six different fictional historians and full of bogus inventions. However, in the case of this particular reign, it seems to preserve an early, first-hand source and gives details absent from the accounts of Cassius Dio and Herodian.

Julianus’s nine-week reign was brief but momentous. He came to prominence during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, entering public life early when he became a quaestor a year before the legal age. The Historia Augusta tells us that he was appointed to a consulship on the recommendation of the emperor when, as governor of Belgica, he repelled a surprise invasion by the Chauci, shrewdly expending auxiliary troops rather than risking his Roman soldiers. Pure luck, it seems, preserved him during the bloody tyranny of Commodus. He was accused of conspiracy; but for once Commodus chose not to believe the accuser, who was crucified for his pains.

After Commodus’s assassination at the end of 192, Julianus found favour with his successor, the popular reformer, Pertinax. The Historia Augusta records that, as Julianus was presenting Sextus Cornelius Repentinus to Pertinax on the occasion of the young man’s betrothal to his daughter, Didia Clara, the emperor declared ‘Honour my colleague and successor’ seeming to designate Julianus his heir.

On 28 March 193 the Praetorian Guards, angered by Pertinax’s attempts to end the license to plunder and terrorise which Commodus had allowed them, shamefully murdered him, after a reign of a mere three months.

According to Herodian, the soldiers, fearing the anger of the people, immediately barricaded themselves in their camp. But, after a couple of days, discovering ‘that all was quiet and no one was brave enough to prosecute them’ they issued an announcement from the top of the wall, promising to entrust the power to the highest bidder’.

The Prefect of Rome, Titus Flavius Claudius Sulpicianus, whose daughter was Pertinax’s widow, immediately offered them 20,000 sesterces each.

Herodian writes that Julianus received the news of the auction while he was in a drunken stupor at a feast. His wife and daughter and a number of clients persuaded him to get up quickly from his couch and run to the camp wall to find out what was happening. All the way there they advised him to seize possession of the empire while it lay abandoned, and by sparing no expense to outbid all possible rivals by the size of his bribe.

The Historia Augusta adds that he was accompanied by his son-in-law, Repentinus, whose father had been the commander of the Praetorians. Herodian paints a vivid picture of the Guards letting down a ladder so that Julianus could climb on to the wall to address them.

He warned them against choosing someone like Sulpicianus, who might decide to avenge Pertinax and then upped the bid to 25,000 sesterces. According to the Historia Augusta, he ‘wrote on tablets a statement that he would restore the good name of Commodus’, and ‘as a result, he was not only let in but was named emperor’. Herodian records that the soldiers gave him the cognomen Commodus, though this does not appear on his coins. Shrewdly, perhaps, he ‘pardoned’ his rival, Sulpicianus, though he replaced him as Prefect of Rome with Repentinus.

On her husband’s elevation, Manlia Scantilla was named ‘Augusta’, and since Julianus had no son and heir, his daughter was given the same title. This gesture towards female equality is unique in Roman history, though the ambitions of Repentinus were presumably the main motive in Clara’s elevation.

It will remain forever uncertain whether Julianus was, as Herodian says, ‘addicted to luxurious and indecent living’, or as the Historia Augusta has it, ‘so frugal that he shared out a sucking-pig over a three-day period, likewise, a hare, if anyone happened to send him one’.

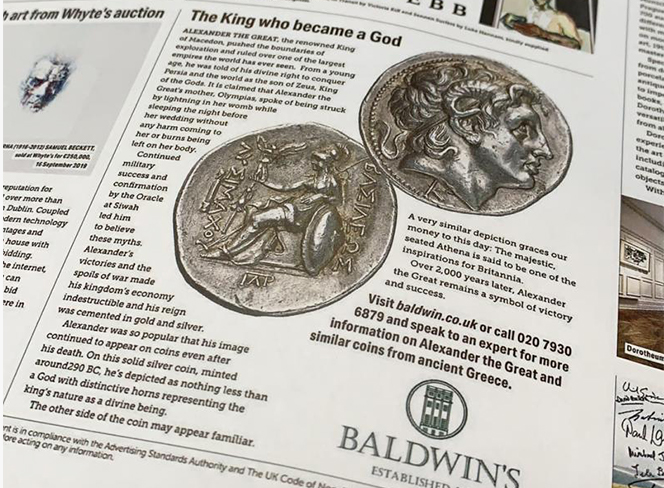

The portraits on his coins give the impression of a man with patrician dignity, but lacking the charisma of an Aurelius or a Pertinax. Ambiguous also are the characters of his wife and daughter. Though Herodian implies that the women urged him on in his foolish bid for power, the Historia Augusta relates that they moved into the palace ‘nervously and unwillingly, as though they already foresaw imminent catastrophe.’

Scintilla’s image on coins varies markedly with the die-cutter, but the sestertius and denarius illustrated here give the impression of a sensible, intelligent woman. Did she and Clara perhaps shrug helplessly as they approached the palace, at this fine mess their husband and father had gotten them into? Or did they indeed, true to the instincts of their class, naïvely revel in the glamour of their elevation?

Any apprehension they may have felt was fully justified. Julianus’s sole support came from the Praetorians and, according to Herodian, he did not in reality, own enough private wealth to pay them what he had promised.

Moreover, the public treasury was virtually bankrupt following the excesses of Commodus, and the new emperor was forced immediately to decrease both the purity and the weight of the silver denarius. It is an indication of the underlying stability and efficiency of the Roman state, however, that, despite this political and financial turmoil, coins struck in Julianus’s name found their way in substantial quantities to every corner of the empire.

At the circus games, a large faction took to chanting the name of Pescennius Niger, an ex-consul and Governor of Syria, ‘who was said to be already emperor’. According to Herodian, hearing the news from Rome, Niger sought support among the legionary commanders and military tribunes.

Popular because of his benign administration, and his sponsorship of frequent circus shows, he was readily proclaimed emperor in his own province. But, according to Herodian, instead of marching on Rome, ‘he turned to a life of idle luxury and enjoyment with the people of Antioch, devoting his attention to festivals and spectacles.’ Julianus sent out a former chief centurion with instructions to murder him.

But Julianus’ nemesis was to come from a different quarter. The governor of Pannonia, Septimius Severus, had a dream in which the emperor Pertinax rode on a fine horse down the Via Sacra in Rome. When he reached the entrance to the Forum he was thrown off, and the horse inserted itself under Severus instead. (It was Severus’s later appreciation of a short book by Cassius Dio on his prophetic dreams that launched the historian on his literary career.) Like Niger, Severus had little difficulty in gaining the acclaim of the officials and troops of his province.

But unlike Niger he then acted decisively, adopting the name Pertinax, and marching on Rome at speed. The desperate emperor sent Aquilius, ‘a centurion well known for murders of senators’, to kill him, and also prevailed upon the Senate to have him declared a public enemy. But, in no time, soldiers loyal to Severus had infiltrated the city in plain clothes, and Julianus’s cause was lost.

There was little he could do. Whatever funds he could gather from his dwindling circle of friends and supporters he gave to the Praetorian Guards. But, Herodian relates, since he had not paid them everything he had promised earlier, they merely took the money as their due. In despair, Julianus made no attempt to guard the Alpine passes, as his advisers told him he must. Instead, he collected together all the elephants in Rome, hoping to intimidate Severus’s naïve provincial troops. According to the Historia, he also ‘had the insane idea of performing a great many acts through magicians’.

Severus seized the fleet at Ravenna and those envoys of the Senate who were in his camp at the time prudently defected. Julianus resorted to diplomacy, sending out ‘the Vestal Virgins and the other priests, together with the Senate, to meet Severus’s army to entreat them with outstretched fillets.’ He proposed a division of power; he pleaded to be allowed to abdicate. But in vain.

The Senate submitted to Severus and sent a military tribune, in Herodian’s words, ‘to kill the cowardly, wretched, old man who had purchased this sorry end with his own money.’ The Historia Augusta is less moralistic:

In a short time, indeed, Julianus was deserted by everyone and remained in the palace with […] his son-in-law Repentinus. Finally, it was proposed that Julianus’s imperial power should be revoked; and revoked it was, and Severus was at once named emperor, while it was pretended that Julianus had taken his own life by poison. Nevertheless, some people were sent from the Senate, by whose efforts he was killed in the palace by a common soldier, imploring the protection of Caesar, that is, of Severus.

Cassius Dio claims that Julianus’s last pathetic words were: ‘But what evil have I done? Whom have I killed?’ The Historia Augusta makes one last mention of his family: He had emancipated his daughter when he gained the empire, and she had been given her inheritance; and this was at once taken from her, as well as the name Augusta. His body was given back by Severus to his wife Manlia Scantilla and his daughter and was moved to the tomb of his great-grandfather at the fifth milestone on the Via Labicana.

According to the Historia, he had lived ‘fifty-six years and four months, and reigned for two months and five days’. Cassius Dio gives slightly different figures.

Repentinus was either killed in the palace along with Julianus or was tidied away subsequently by murder. Sulpicianus was executed four years later, in 197, for plotting against Severus. Were Manlia Scantilla and Didia Clara perhaps, spared to live out a sad old age on an estate in the Campania? We are not told.

This article by James Booth is an excerpt from the Fixed Price List: Summer 2019.