The Rise and Fall of a British Bare-Knuckle Boxer

Whilst scouring through some of the fascinating items found within The Deane Collection of 17th & 18th Century tokens auction we stumbled across Lot 199. This 1789 Penny/Medalet from Banbury may seem innocuous at first glance, but has a history that could make it one of the knock out items from this collection as it features the portrait of British bare-knuckle British boxer, Thomas Johnson, who was referred to as the Champion of England between 1784 and 1791.

The story of Tom Johnson is not an uncommon one amongst boxers, the story of a champion whose life breaks down has been echoed by many a past great, including Heavyweight Champion Leon Spinks, the youngest world champion in boxing history Wilfredo Benitez, and even the great Raging Bull, Jake LaMotta. The one thing that does make this story uncommon is that none of those fighters ever had their own currency!

Prize fighting had become a popular sport in the eighteenth century and Thomas Johnson’s prowess in boxing gave him public recognition and national fame. His success was largely due to his technical ability, his analytical approach, his calm and not just his very great strength.

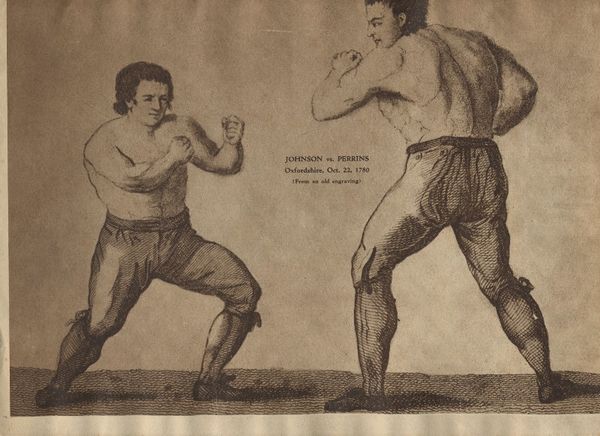

In October of 1789, at Banbury, Johnson fought Isaac Perrins from London, nicknamed the ‘knock-kneed hammerman from Soho’ and it is to this outdoor event, attracting some 4,000 spectators, that this coin owes it’s existence.

The contest was billed as a battle between Birmingham and London as well as for the English Championship. The two men were much the same age (late 30s) but very different in physique – Johnson was around 5”8’ weighing 196lbs. and Perrins taller at 6”2’, weighing 238lbs. Johnson was smaller but nimble and artful and Perrins was larger but naïve and bull-like.

After 75 minutes of 65 rounds the exhausted favourite, Isaac Perrins was defeated and it is recorded that “his face had scarcely the traces left of a human being”. Both Johnson and Perrins received 250 guineas for participating and Johnston received 2/3rds of the some £800 taken at the gate. In addition, Johnston received ‘gifts’ from happy supporters who had bet on him, particularly £1,000 from a Thomas Bullock who reportedly won £20,000 from a successful wager!

Unfortunately, Johnson was not so successful outside the ring – he was an inveterate gambler and generally seen to be easy prey for the ‘sharper’ players. Undoubtedly, he earned a great deal of money from boxing, in fact he earned more than any other fighter at the time – or for that matter for the next fifty years, he just wasn’t very good at keeping hold of it.

…it is recorded that “his face had scarcely the traces left of a human being”

After his retirement in 1791 he bought a public house, The Grapes, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. His establishment soon became known as a haunt of gamblers and criminals, losing Johnson his licence to operate the premises. Subsequently he sought wagers at horse race meetings and cockpits, refusing to pay if he lost and instead challenging the victor to a fight. His deterioration was rapid. Both his health and his spirit were broken and just a few years later he died a poor man with virtually all of his very large wealth squandered.

And this would usually be where this story ends, but with a handful of these coins (among other fight game objet d’art) still circulating and sparking tales of his great battles from back in the day, his legend was never really allowed to fade and in 1995 he was inducted into the Pioneer category of the International Boxing Hall of Fame.