The Venetian Grosso or Matapan was a silver denomination first introduced in Venice in 1193 under Doge Enrico Dandolo. Upon its conception, the Venetian Grosso contained 98.5% pure silver– the purest silver coin in Medieval metallurgy. These coins played a significant role in the economic prosperity of Venice, especially in international trade and funding of the Crusade Wars.

Introduction of THE Grosso in Venice

Before the introduction of silver Grossi, Venice struck silver denari based on coinage of Verona that contained less silver of lesser quality. These Veronese counterparts were used primarily for domestic trade. For foreign trade, Venetian merchants preferred Byzantine coins or coins minted in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was not until Doge Enrico Dandolo that the coinage of Venetian Republic was reformed and improved. He introduced a higher denomination of fine silver called a Grosso. The name came from the term Denaro Grosso (large penny), also known as Matapan for the Muslim name for it. These new Grossi had major advantages over the older denominations; their minting and handling cost was lower and the higher purity of silver made them suitable for international trade.

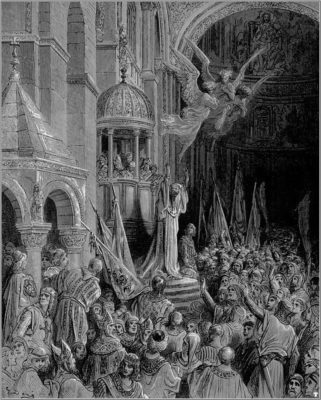

Some scholarship suggests that the Venetian Grosso was introduced to pay for the ships needed for the Fourth Crusade, to transport the crusaders at the very beginning of the 13th century. Even though the coin was introduced some years earlier, it is safe to say that the costs and economy of the Crusade Wars led to its prominence and mintage on a large scale. Dandolo played a significant role in the promotion of the Fourth Crusade which led to the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and rise of Venice. It is interesting to imagine the rising power of Venice in parallel with the image of its distinguished leader Enrico Dandolo. He is described as always on the front line of battles. It is said that at the conquest of Constantinople, he stood in the bow of his galley, armed and with the gonfalon of St. Mark’s in front of him. Indeed a powerful image and connection with the patron saint of Venice conveyed on the coinage too.

The iconography of silver Grossi

View the coin

These coins were a part of a wider range of reforms by Enrico Dandolo to strengthen the trade with the East. On the obverse, there is doge, wearing a cloak and holding the ‘ducal promise’ while St. Mark, the patron saint of Venice, presents him with the gonfalon (banner). The legend on the left is the name of the doge, with his title DVX in the field. The legend on the right is S. M. VENETI – St. Mark of Venice. The reverse shows Christ enthroned, facing, with Greek abbreviation of his name: IC XC. The beaded border of these coins served to prevent clipping as a security measure. As another measure, doge Jacopo Tiepolo (who ruled from 1229 to 1249) added variations in the punctuation in the obverse legend and small marks near Christ’s feet on the reverse, which also served as mintmarks. The iconography of grossi remained the same for more than 150 years, with only minor changes.

View the coin

However, in the late 14th century, the cost of silver increased which forced some doges to issue fewer Grossi or to stop issuing them altogether. The Grosso of Antonio Venier pictured above dates from this later period. In the oncoming centuries, their weight continued to fall significantly.

The influence of Grossi outside of Venice

Soon the popularity of silver Grosso rose and the other Italian mints started issuing their own versions. Among others, Verona, Bologna, Parma and Pavia all had coins of pure silver by 1230. Venetian Grosso became an important currency in the international trade known around the world for its quality. Imitations and forgeries became commonplace, especially in the parts under Venetian influence and rule such as Dalmatia. In Western Europe, the monetary system was based on the penny, a new era of larger silver and gold coins began; denominations that we know as groschen and groat all derive from the innovation brought upon by Venetian Grosso.